The morning after the install, the gallery had that strange hush, like a theatre before curtain-up. Everything was ready, but nothing had begun. We spent the whole day scrubbing, checking, re-taping things (again), touching up smudged walls, and wiping every damn surface more times than I care to admit. Linda was doing last-minute surgery on her Amazon sculpture after spotting what she called a “major flaw”—which, in reality, was just a few stitches that had come undone. Roman nearly lost it when he discovered a dodgy speaker cable an hour before soundcheck.

By half five, the place was gleaming. Every cable was taped flat, every plinth buffed, every exhibition label aligned with sniper-like precision by Elin. The flyers were stacked neatly. The bar staff were already pouring prosecco at the front desk. Kayla’s haunted nervous system installation pulsed in pitch-black silence. Zoe’s canvases were lit like sacred objects. Linda’s Labour Love Lies banner hung by the entrance like a protest flag.

At six sharp, the preview began.

We’d done it properly—invite-only, with names on a clipboard at the door, checked by one of Rex’s mates in towering New Rock boots and a hacked-up Matrix coat. He took his guest list duties very seriously. The crowd was a motley mix: broadsheet editors, arts journalists, cultural critics, east London DJs, bloggers, one reality TV presenter who thought it was a pop-up cocktail bar, and someone claiming to be Banksy’s cousin.

And then there was Cressida.

She arrived with the kind of confidence only someone who’d once told David Hockney he was wrong could carry. Dripping in pearls and kaleidoscopic silk, she moved like royalty, but with a glint in her eye that said she could drink you under the table and dismantle your worldview in a single sentence.

When some stuffy Telegraph journalist sniffed at Linda’s banner and muttered something about “pop-up trash,” Cressida turned to him slowly, like a lioness stretching before a kill.

“Do you know what’s trash, darling?” she said, her voice smooth as brandy. “A country where workers’ rights are unravelled like old socks and young artists are priced out of their own cities. That’s trash. What Linda’s doing is responding to that. With courage. With teeth.”

He tried to reply, but she cut him off with a smile so elegant it should’ve been framed.

“I’d love to introduce you to her,” she added sweetly. “But she’s busy being relevant.”

He disappeared shortly after.

Cressida, meanwhile, was in her absolute element. She floated from room to room, stopping people with a gentle tap on the arm to explain the symbolism in Rex’s couture stitching or the inner logic of Kayla’s installation. She’d done her research. She knew the work. She made the old guard listen, not just out of politeness, but because she made them want to.

Arabella was a blur of energy—as always—hugging, laughing, welcoming everyone from blue-chip collectors to old-school punks. Somehow, she knew everyone’s name. Or guessed convincingly.

Kayla’s installation was a quiet triumph. Once inside, visitors were immersed in a strange, glowing experience—pulsing light, layered sounds, chaotic narration. She’d even designed a scent for it: crisp, clean, like air after a thunderstorm but tinged with bleach. People emerged looking equal parts impressed and disturbed. Someone asked, semi-seriously, how much it would cost to buy. Kayla turned sheet-white and ran to Jac.

“I didn’t think anyone would actually want it,” she said, half-laughing, half-panicked. “I thought it was, like... too much. Too me.”

Jac just smiled, calm as ever. “They always want too much ‘you.’ That’s how you know it’s working.”

Her girlfriend Lou handed out postcards with a QR code—designed in the shape of a brain—linking to a docu-journal of Kayla’s process, from skip-diving to sleepless nights with a soldering iron.

Zoe and Smike barely left each other’s side. When a gentle arts reporter asked Zoe about her paintings, then quietly said, “I’ve lived through the same thing,” the two of them just hugged. No words. Just a seismic moment of stillness.

Smike’s slideshow-poetry piece had a gravitational pull. People were asked to limit their time because no one wanted to leave. There were tissues nearby. They were needed.

In the first room, Linda held court from her purple yeti fur ‘thinking chair,’ spinning wild, brilliant rants about feminist theory, hierarchical failure, and the ghost of Thatcher. Someone from a think tank took notes. Someone else offered her a podcast deal. She pretended not to care but didn’t say no.

Rex looked like a walking piece of his own work—stitched slogans, custom hardware, everything handmade. His mannequins stood like defiant saints. He handed out block-printed patches to anyone who promised to “stitch it on something real.”

Elin’s photo wall drew a kind of reverent hush. A collage of faces, fragments, a year of laughter and paint and grit frozen mid-flight. One woman stood in front of it and whispered, “This whole thing... it’s got a soul.”

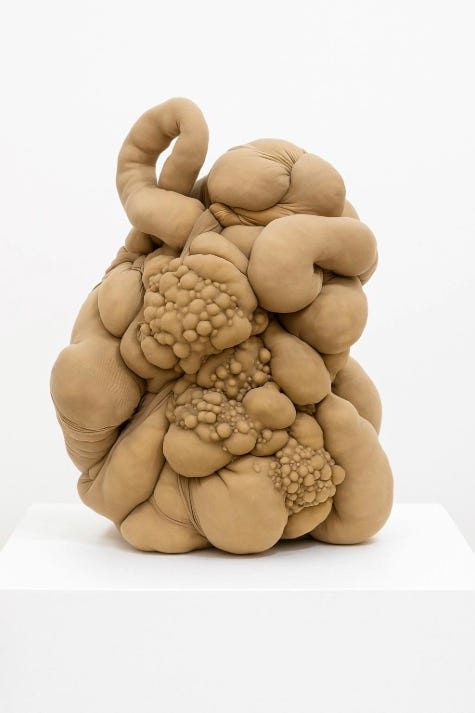

Arabella’s soft sculpture—entitled Beautiful Deformity—sat on a plinth like an accidental mascot. She claimed she included it mainly to shout out the art collective in Berlin.

And then there was my little corner—Kasia’s Story. One small plinth, a cut-out collage, a laptop open to a journal entry I’d written on the coach to London, and a prompt: “What happens next?” People queued to write. Scribbled wild, aching, beautiful things. Notes of hope. Stolen dreams. Jokes. Truths. By the end of the night, the document had over sixty entries.

I cried quietly in a corner.

Malik kissed my forehead and said, “Told you.”

Roman floated through it all—adjusting the lights, fine-tuning the music, chatting with everyone. One moment he was refilling water glasses, the next he was explaining a jungle drum break to a guy in a tie who’d never heard it before.

And Jac… Jac did the gallery owner thing. Calm. Polished. Managing egos. Calming nerves. Whispering encouragement. Making space for the rest of us to shine. He was very good at it.

By the time the prosecco ran out and only the stragglers and diehards remained, we gathered in the centre of the gallery. Arabella burst into tears—proud, exhausted, prosecco-sparkled tears. We wrapped her in a group hug that somehow pulled in everyone.

Cressida stood at the edge of it all, smiling like she’d just remembered who she used to be.

“One night down,” Jac said softly. “Two weeks to go.”

But we didn’t care.

That night, we’d done it.

The Nest had landed. And the world was watching.

- Kasia W